Fear-Setting for Risky Decisions: From Uncertainty to Action

Fear-Setting for Risky Decisions: From Uncertainty to Action

Moving from Amorphous Uncertainty to Action

Leaving the structure and security of the military, I had no roadmap. There was no manual for navigating job boards or translating years of disciplined problem-solving into “junior engineer” on a resume. Evenings felt endless, staring at listings I wasn’t sure I’d understand, let alone qualify for. And underneath every search: What if I failed? What if no one hired me? What if I wasn’t cut out for this?

The fog of those questions weighed on every decision. But fear-setting changed how I moved. Once I put my worst-case scenario in plain language—relying on my military background and picking up contract work if I had to—the paralysis cracked. That wasn’t the life I wanted, but it wasn’t disaster.

Quantifying my risk did something practical. A temporary step back was a 3 or 4 out of 10, not a career-ending catastrophe. Suddenly, recovery felt feasible and I started making choices with real momentum. That was when I discovered Tim Ferriss’s fear-setting framework, and it turned a guessing game into a plan I could follow.

That’s the promise behind fear setting for risky decisions that I want to unpack here. When we get concrete about failure, build plans for it, and measure what standing still costs, we can bring the same clarity to engineering and AI decisions—especially when moving forward feels risky.

When Unbounded Fear Holds Progress Hostage

If you’re leading an infrastructure overhaul or making AI product risk decisions, you’ve felt the freeze. The conversation circles. What if migration breaks core services? What if the new tool blows up costs, or worse, doesn’t fit? The pressure to get it right means risks swirl unnamed around the table, and nobody wants to guess wrong and derail everything. You know what stalling feels like. Debates that drag, “let’s wait for more data,” no real decision ever landing. It’s familiar, but costly.

The trouble is, sticking with the status quo often feels safe, but it rarely is. Teams default to what they know because status quo bias comes down to cognitive misperception, rational decision making, and psychological commitment—all of which keep teams in place even at a cost. This isn’t just habit. It’s a natural bias that tricks smart engineers into thinking inaction is protection against risk, when really it sometimes buries risk deeper.

There’s also the fear that, if we try to label failure points or forecast outcomes, we’ll land in “false precision”—mapping guesses as if they’re facts. I get it. If you’ve ever pitched a risk map in a room of engineers, you know half the battle is admitting, outright, that you might not be right. But inertia is a risk too. Naming what could go wrong doesn’t make you fragile. It starts moving you out of gridlock.

Fear-setting works because it elbows aside those vague anxieties without pretending you’ve solved everything up front. When you make risks explicit, lay out possible mitigations, and balance real upside against the weight of sitting still, you see blind spots that otherwise lurk in groupthink.

Naming explicit scenarios and mitigations actually cuts down failure from blind spots and cognitive biases, especially overconfidence. It’s not about forecasting with perfect detail. It’s about seeing the worst case, poking holes in your strategy early, and catching the avoidable errors now—not months down the line, when stakes are higher and options have narrowed. Fear-setting won’t remove risk. But it reframes it, giving you a clear canvas to paint your real options and decide, eyes open, what’s worth doing.

Next time you find yourself stuck at the edge of a technical bet, try dropping the abstract anxiety and mapping out those concrete risks. You’ll be surprised how much clarity you unlock—right when stakes matter most.

Building Your Risk Map: Steps to Clarity and Action

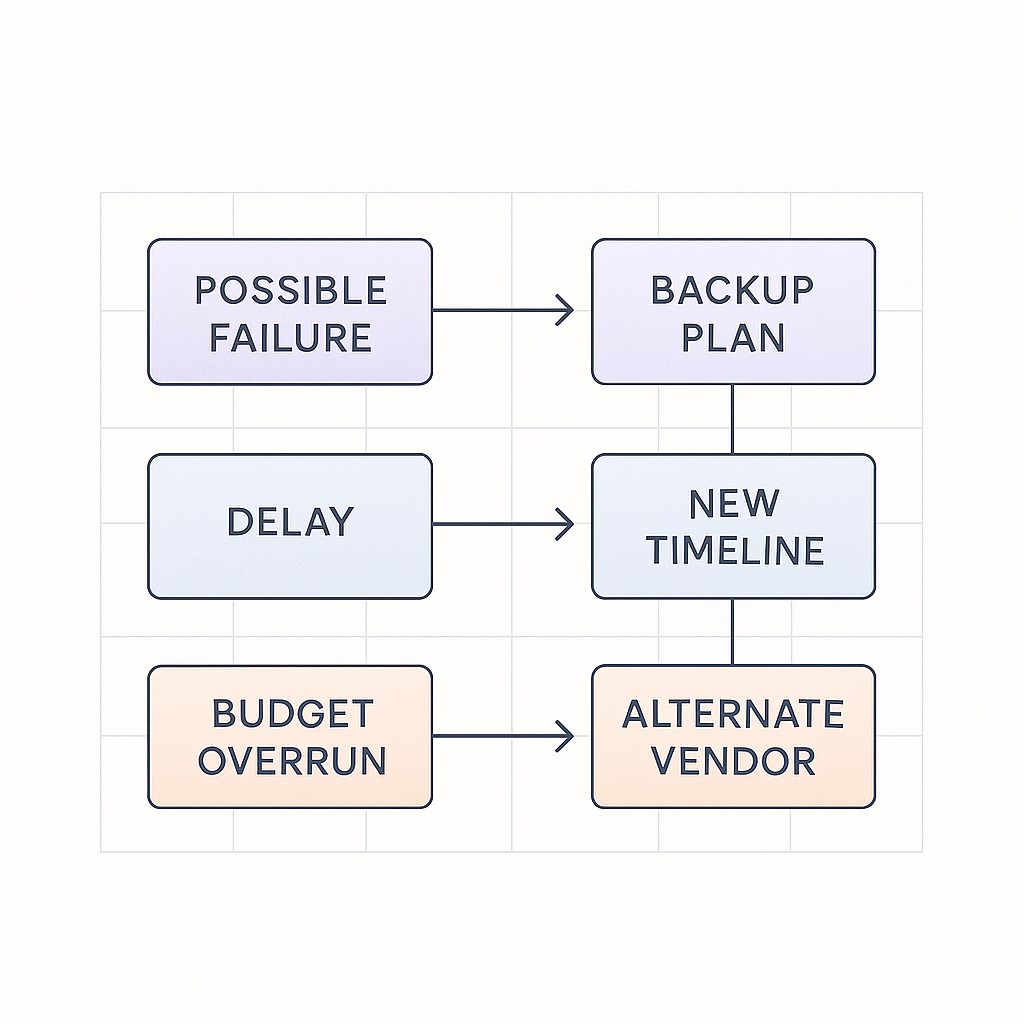

Here’s the nuts and bolts of a fear setting exercise. Lay out the major steps in plain language. First, actually name your concrete failure scenarios. Don’t settle for “something might break”—call out the specific system, the real consequence, and when it could happen. Next, make the impact granular. Who does it hit, and for how long? After that, line up mitigation steps. What tools do you have to soften the blow if it happens? Then, weigh the upside. What do you gain, in throughput, speed, reliability, or cost if things go right? Finally, include an honest line about the cost of inaction.

Put these factors into a simple risk matrix (and consider risk-tiered validation as mitigation as an applied pattern) and suddenly the noise quiets down and choices snap into sharper focus.

But how do you take a vague fear like “this upgrade will crash production” and turn it into something useful? Ask pointed, time-bound questions. Okay, but how exactly would it crash? Would it be a five-minute outage, a loss of data, or just some angry emails? Who gets hit—internal ops, end users, paying customers? For how long could we tolerate that pain before it’s truly damaging? And what’s the real consequence: is this a rollback and apology, or a month rebuilding lost trust? Make each risk specific enough that you can picture tracking it in a Jira ticket or postmortem. When you put that level of detail on the table, conversations shift—less hand-waving, more real planning.

Now, take those failure modes and draw a clear line to mitigation steps. Early detection with logs and alerts, patching after the first error, a rollback plan ready to go, and, if needed, public ownership when things go off track. You don’t need perfection, just resilience. When you map the recovery before it’s needed, it recalibrates everyone’s confidence and moves the needle from paralyzed “what if” to real readiness.

Don’t forget to quantify cost of inaction and ballpark the upside just as rigorously as the downside. What happens if it works—do you boost throughput by 2x, cut manual error in half, unlock speed for other teams? Use honest ranges (“20-40% drop in alert noise”) and thresholds (“must release by Q2 to hit target”) instead of wild guesses. Equally, spell out what you’ll lose—be it slow progress, mounting technical debt, or missed business windows—if you hold off. These numbers, even if rough, push the conversation from “maybe” to informed judgment.

Just as an aside, I still occasionally find myself obsessing over some unlikely risk path. Last month, during a greenfield deployment, I lost nearly an hour double-checking CLIs and second-guessing shell history, convinced I’d push to prod instead of staging. Turns out, the safety net was there—I just hadn’t reviewed it up close since onboarding. That habit of naming and walking through each step, even on autopilot tasks, is what lets me shift back from spiraling to actually making the next move.

When the worst is on paper, it rarely controls your next step.

Applying Fear Setting for Risky Decisions to Real Engineering Decisions

Let’s ground this in something concrete: say you’re staring down a system overhaul—the sort where database changes, new services, and unfamiliar integrations all collide. It’s tempting to generalize the fear as “breaking production,” but that just freezes everyone. Instead, walk through it bit by bit. List out the plausible failure points (like data loss when swapping tables, or rolling deploys stalling a service). Name exactly what would break, how long downtime could last, and which customers would feel it. Add what you’d actually do—like running dry runs, setting up rollbacks, sandboxing changes, and making on-call rosters explicit. Once you’ve bounded the risk and tagged real mitigations, you can move forward—often faster—because the unknowns feel sized, not infinite.

Let’s talk deployments, because “it might break” ends up paralyzing more projects than outright technical missteps. Instead of treating “production breakage” as a binary, get surgical. Will an error cause a total outage, or just spike error rates for five minutes? Will ten users see a glitch, or ten thousand? How much revenue do you put at risk per minute?

Spell out the human and systems impact. Who gets paged, what notifications customers see, and what the actual rollback window looks like. An outage with clear rollback and comms channels is a nuisance. An outage with “no one knows who owns the fix” is a career risk. The more you specify—duration, blast radius, communication plan—the more realistic your assessment gets. Suddenly the monster under the bed looks a lot more like a paint-by-numbers risk that you already know how to tackle.

But clarity isn’t just about the plan on paper. It’s what aligns the team. As part of worst case scenario planning, you set up Plan A (the preferred success path), Plan B (the fast recovery if something misfires), and Plan C (the list of steps for worst-case recovery or retreat), and, where appropriate, let risk decide POC vs product. You don’t have to pretend you’ve covered every edge case. You’re just showing the team—and yourself—you’ve thought far enough ahead that everyone can focus on the build, not just the fear.

This framework isn’t chained to technical launches. Try it during org redesigns or when you’re about to choose between building on Kubernetes or betting on a cloud vendor you’ve barely tested. Name the risks of a team split: slower onboarding, duplicated effort, or culture drift—and counter with safeguards like shared onboarding docs and explicit comms. For infrastructure moves, label specific fears (vendor lock-in, migration overhead) and lay out mitigations (abstracted interfaces, bake-off periods). When teams see risks turned into shared, named problems—not lurking question marks—alignment speeds up and progress gets real.

Back in that first section, when I mentioned fearing even a basic job search, what I didn’t realize was that it’s not all that different from tackling a scary migration or high-stakes launch. Different stakes, similar process. That clarity turned fear into fuel. And if I’m honest, sometimes I still catch myself hesitating—even after years of doing this work. I know naming risks doesn’t kill the nerves every time. Maybe it never fully does. But it keeps me moving—eyes open, guessing less, planning more.

Here’s where fear setting for risky decisions pays off. You stop “just guessing.” You’re not throwing darts in the dark or gambling with the business. By naming scenarios, sizing impacts, and shaping fit-for-purpose responses, you’re making leadership concrete—defensible, deliberate, and resilient, no matter how big the technical bet.

If you’re a builder who needs to share plans, updates, or docs fast, use our AI to turn rough notes into clear posts, briefs, or emails in minutes.

Clearing Common Roadblocks—And Getting Started, Fast

I know the objection. “We don’t have time for all this risk mapping.” Six months ago I probably would have nodded along, especially near crunch time—it always seemed faster to just push ahead and cross fingers. But every time we skipped this, we spent more hours in messy rework, retracing steps, or debating the same issue again. Here’s what changes when you get concrete early. Framing cuts down back-and-forth, which stabilizes outputs and saves you from circular discussion.

It’s also normal to hesitate before exposing all the risks. No leader, especially in a new domain, likes to announce every possible failure. But when you put risks on the table, it doesn’t scare people off. It actually builds trust. You’re not claiming to avoid every pitfall. You’re showing you’ve thought them through and have a plan, which stakeholders respect.

If you want the quick-start version, here’s the structure I use now: scenarios (what could go wrong), impacts (on who, and how bad), mitigations (how we’d respond), upside (real benefits), cost of inaction (what standing still loses), and Plan A/B/C. Start small. Pick one or two scenarios and iterate each round. It’s enough to unlock clarity right away.

You don’t have to overhaul your whole process—just try this once on your next high-stakes decision and see if the fog lifts. Taking ten minutes to name and plan for risks is what moved me from guessing to deliberate action. Give it a shot.

And for what it’s worth, I still revisit some of these frameworks myself, even now. There are days when I map out a risk, make a plan…then scrap it all because the ground shifts or I miss something obvious. I haven’t entirely solved for that tension, and maybe I never will. But each time, at least I know what I’m reacting to—and that’s usually enough.

Enjoyed this post? For more insights on engineering leadership, mindful productivity, and navigating the modern workday, follow me on LinkedIn to stay inspired and join the conversation.

You can also view and comment on the original post here .