How to Write for Stakeholders: Clarity That Speeds Decisions

How to Write for Stakeholders: Clarity That Speeds Decisions

Words That Stick: Why How You Write Shapes Everything

The lesson landed with one misstep—and it hasn’t faded. I remember the day I sent a quick update to an exec, typing fast, focused on accuracy, and assuming they’d “get it.” The reply back was polite but unmistakably stiff, the virtual equivalent of a raised eyebrow. I’d chosen my words for myself—efficient, a little terse, shorthand that made sense to me and maybe my team on a tired Wednesday. It felt fixable, so I followed up and tried to clarify.

But every time we interacted after, there was this ripple: I was “that engineer.” The one who came off a bit sharp, harder to read, less of a partner. That’s when it hit me—messages aren’t lines of code. You can refactor all you want, but the human on the other end has already run your program. The impact burns in, even if you go back and push a “better” version later.

That’s the real difference. Bad code can be rolled back. But a poorly worded message? That can stick with you long after the issue is resolved.

I’ve watched teams, including ones I’ve been part of, repeat this again and again. It usually starts with someone who hasn’t learned how to write for stakeholders—so they write exactly what they think, for themselves, with all the right technical facts, and leave out how it lands for the person reading it. Maybe a feedback request shows up blunt or unclear, or an update gets buried under details nobody else needs. The next thing you know, someone’s confused, decisions slow way down, and what should have been a small hiccup drags out for days. Most of us aren’t rude on purpose. We just forget we’re writing to a person, not logging an error.

Here’s the heart of it. Shifting your writing, even just a bit, from your comfort zone to what helps others decide and act—that’s how things start to move. If you treat writing like talking to a compiler, you miss what makes things work in teams. Write for people, not machines, and the results start to look very different.

Just once, early in my career, I thought none of this really mattered—as long as the facts were right, the rest would take care of itself. That theory lasted about a week.

Stick with me here. By the end, you’ll be able to write messages that give any stakeholder what they need in one read: clear, respectful, and direct—so they can move forward quickly, and you can get back to building.

Write to the Reader, Not Just to Yourself

Audience-centered writing tips are all about making the reader’s decision easier, not just getting your ideas out of your head. It’s designing your update, your ask, your doc, to match how the person on the other end actually makes sense of things. “Clear to me” isn’t the same as clear—especially not when someone has five minutes between calls and needs to figure out their next step fast. You can spot audience-centered writing when you read something and immediately know what you’re supposed to do. That’s the goal: move from “I think I explained it” to “the reader knows exactly what matters and what to do next.”

Tone is the invisible carrier of intent, something coding never prepares you for. In writing, tone does what body language can’t. If you don’t shape it deliberately, people will fill in the gaps themselves, and rarely the way you wish.

The higher you go, the more this matters. When you’re shipping code, maybe only two teammates see your notes. As you start leading projects or talking with execs, every sentence moves through rooms you’re not even in. A single off-note, a phrase that can be read as dismissive or vague—it can derail alignment or stall progress for days. The higher you climb, the more your influence depends on strong engineering communication skills, not just how well you build.

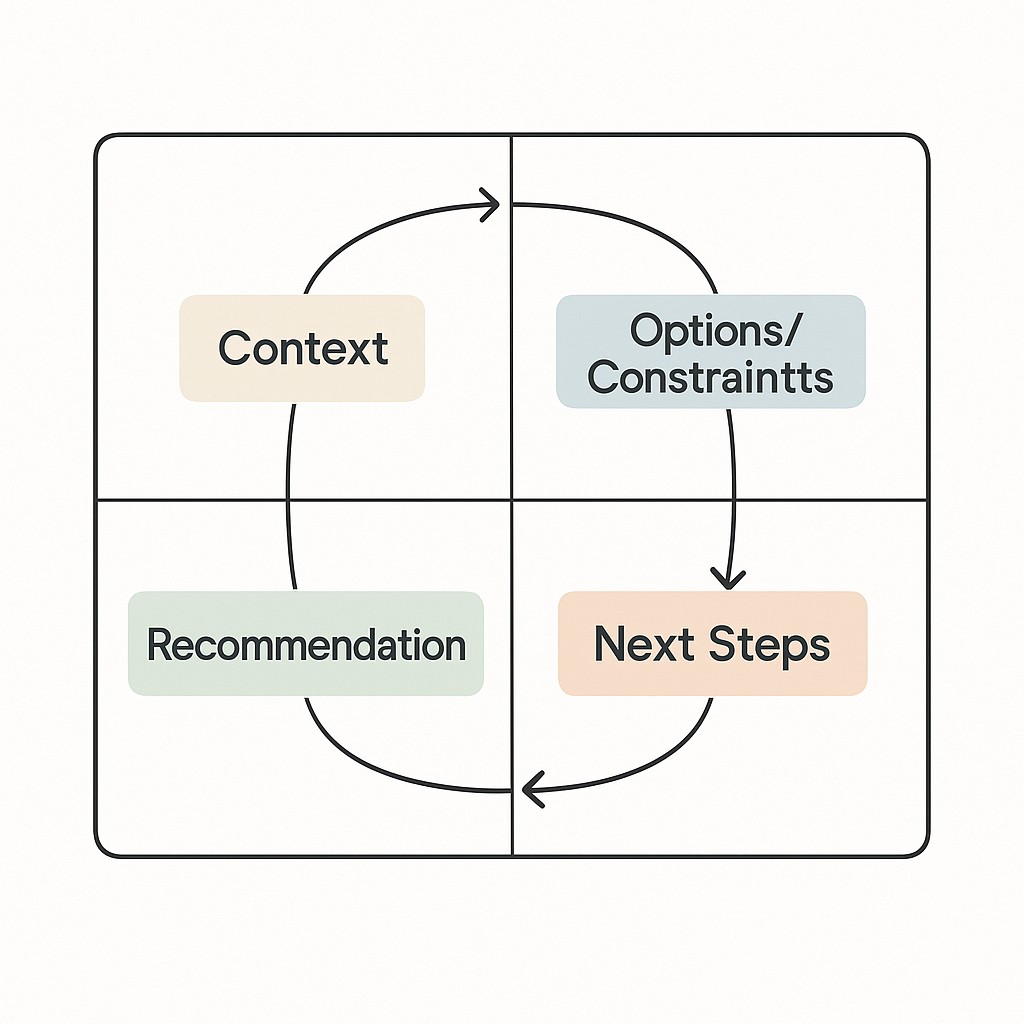

Here’s what’s really happening: decision-makers scan your message for four things. Enough context to get their bearings, the real options or constraints, what you’re recommending, and exactly what you want them to do. Make those things painfully easy to spot, and you’re halfway home.

One technique that made a difference for me is to think in terms of a quick structure borrowed from healthcare. SBAR provides a structure for spotlighting context and clear recommendations, enabling quick, high-stakes decisions, alongside storytelling that earns buy-in to translate features into outcomes and pilot-ready action. When I switched to this method, my updates went from “here’s everything I’m thinking” to “here’s what’s happening, what I’ve checked, what matters, and what I’m asking for.” Suddenly, decisions that dragged out for days started moving in one thread. The bottom line. Clarity isn’t nice-to-have, it’s an accelerant.

Docs, decks, briefs—they’re not just outputs. They’re leverage. Every piece of writing either bogs things down or helps move entire teams and decisions at scale. If you want impact, treat every message as one of your primary levers.

Step-by-Step: Writing for Decisions, Not Just for Output

Start every message by asking yourself a simple but surprisingly rare question: How will I write to influence decisions? Instead of typing what’s in your head, map what the decision-maker needs—constraints, likely questions, preferred format, even the tone they expect on a busy morning. Don’t just broadcast facts; answer the questions they’ll inevitably ask. I used to think my main job was to ship code. Now most of the work is shaping info so people can move. Write like decisions depend on it, because they actually do.

Clarity is your engine here. Subject lines that pull out the actual issue or request—none of that “Quick Update” vagueness. Start with a TL;DR. Two lines summarizing the situation, options, and what’s needed next. Lay out choices in plain sight, frame up the tradeoffs (so no one has to hunt for the downsides), and when you ask for something, say explicitly who’s responsible and when you need it. Even with technical docs, the fastest way to keep things moving is to get everyone past the “wait, what exactly do they mean?” phase.

A note for emails—sometimes I write the TL;DR after the main text, then use AI to tighten updates and copy it up top once I see how long the draft has gotten. Trust me, it buys you goodwill.

Tone matters as much as content. Default to direct respect and curiosity—be specific, but avoid loaded words or sharp edges. I used to worry that making things “softer” would dilute my message, but it turns out, firmness with kindness lands far better. Cut the fluff, not the kindness. People move quicker when they aren’t bracing for something dismissive. If you’re making an ask, be bold but frame it as a request, not a demand. Sometimes all it takes is “Could we decide on X by Friday?” instead of “Need X done.”

Adapt writing to audience and to the artifact. What works in a PR—concise change summary, direct checklist—won’t fly in a planning doc where teams need context and rationale. Recognize that what works in a PR doesn’t work in a planning doc, prompting a shift to match depth, voice, and format to audience and purpose. The more you see the gap, the easier it gets.

Here’s a weird tangent. My coffee maker beeps until I press the button. Total machine behavior—precision wins, not patience. But people? They notice when you shape your words for consideration, not just for accuracy. Machines reward precision; humans reward awareness. That’s the real lever.

My editing ritual changed everything. I read my draft once for scan path—what signals jump out for someone skimming. Once for tone—is this clear and collaborative, or dry and vague? And a last time for the ask—can a reader decide in one go? Most people scan new content for key signal; only 16 percent read everything word-by-word NNG Group. I decided to edit like I respect people’s time. It’s a habit worth picking up.

How to Write for Stakeholders: Applying Audience-Centered Writing to Everyday Engineering Work

Let’s start where the stakes are highest: executive emails. If there’s one lesson that’s imprinted, it’s this—leave the context and the ask up front. Whenever I write to an exec now, the first lines spell out “Here’s what’s going on, here are two paths with the tradeoffs, and here’s what I need from you by Friday.” No buried asks, no mystery around next steps. This is exactly what I missed in that infamous email—my update looked like a status dump, and the decision needed wasn’t clear. That’s how you end up as “the engineer who’s hard to work with.” Save the recipient the confusion, save yourself the long-tail perception hit. If your message helps them decide in one read, you did your job.

Planning docs, decks, briefs—they’re not about showing everything you know. Instead, start with a sharp problem statement. When writing for nontechnical stakeholders, layer in only the constraints, the viable alternatives, and then your honest recommendation. The supporting details go into appendices; that way, the main thread makes sense to a reader skimming at speed, but the depth is there for anyone who needs it.

In PRs—and I wish I’d learned this sooner—put the intent and potential impact at the top, not buried in code diffs. If your change is risky, say so. If it unblocks something big for another team, make that explicit. And with feedback, specificity wins. “Here’s one thing to adjust, here’s why it matters, and here’s a concrete next action.” I’ve misfired plenty, leaving vague or blunt comments that were totally misunderstood. The right comment avoids the tone misread that slows down work, and it sets up the team to actually improve—not just guess what’s wrong.

There are days (honestly, too many) where I look back and wonder why I still default to writing what’s clear to me and not to the reader—especially when the stakes are high. I know it’s the wrong move, but muscle memory is stubborn. Maybe that’s something I haven’t figured out how to fully break.

Writing AI prompts now feels eerily familiar—treat them like you’re briefing a teammate in a rush. Spell out your objective, clarify any constraints, drop examples, and state how you’ll check if the answer is useful. The more you structure your prompt, the fewer times you find yourself re-explaining what you meant, to a model or a colleague.

If you shape each of these artifacts with the reader’s decision in mind, friction drops. The goal is always the same. Let the other person move after one read. That’s where the influence—and faster results—actually begin.

Making Audience-Centered Writing a Habit—And Handling the Doubts

Let’s tackle the biggest objection first: time. Every engineer I’ve coached worries about the extra hours audience-centered writing will take. I used to feel the same way—why spend twice as long on an email or doc when the code is piling up? But here’s the compound return. One careful draft, shaped for your reader, can end a string of confusing replies, unblock a stuck decision, and save you—and everyone around you—weeks of slow cleanup. Trust me, I’ve seen projects stalled out just because someone had to keep clarifying what actually needed to happen. Clear writing is a lever, not a tax.

And it’s not just anecdotal; poor internal communication costs large companies an estimated $62.4 million per year in lost productivity and opportunities SHRM. In reality, every time you write once instead of fixing weeks of misreads, you’re reclaiming speed and reputation—two things that always pay back.

Now, about the fear of sounding political. Most engineers I know bristle at the idea of “spinning” their words—they want to be direct, not diplomatic. Here’s the reframing that changed things for me. Being clear and considerate isn’t manipulative; it’s simply making sure your intent lands as you mean it. Influence grows from honesty and respect, not clever phrasing or hiding the ball—and you can influence without raising your voice.

Worried about losing authenticity? You’re not alone. But being authentic doesn’t mean writing only for yourself—it means making your thinking legible for others. “Clear to me” is a comfort trap; the work is in making your meaning so clear that others can act on it, not just nod along.

Build clear, reader-focused updates, briefs, and prompts with AI, so decision-makers get what they need in one read and you get usable drafts in minutes.

So commit to this. Intentionally treat your writing as a lever for impact and document impact with a steady cadence. Write for the actual people reading, not just to clear your own head. One careful draft, shaped for your context, saves your reputation, your time, and your progress every single day.

Enjoyed this post? For more insights on engineering leadership, mindful productivity, and navigating the modern workday, follow me on LinkedIn to stay inspired and join the conversation.

You can also view and comment on the original post here .